Mustang Shorelines

Shorelines are the dynamic boundary between land and water. The Bureau maintains a digital database that contains numerous shoreline positions for the Gulf of Mexico coastline and select Texas bays that are used to calculate rates of shoreline change. These shorelines come from numerous sources including photography, GPS, and lidar.

Shorelines used in older Bureau studies were mapped directly on aerial photomosaics (quadrangles) then optically transferred to 1:24,000 scale, 7.5-minute USGS topographic base maps (Caudle and Paine, 2024; Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021). With the advent of ArcGIS, those paper maps were scanned to create a digital file, then imported into ArcGIS, georeferenced in NAD27 (datum of the USGS topographic maps), and transformed into the NAD83 coordinate system. The shoreline positions were then digitized in ArcGIS. The 1995, 2007, parts of the 2016, 2020, and 2022 shorelines were mapped digitally within GIS by digitizing the wet beach/dry beach boundary as depicted on high-resolution, georeferenced aerial photographs. The 1996 Gulf shoreline was surveyed using differentially corrected GPS data acquired from a GPS receiver mounted on a motorized vehicle. Shoreline positions were extracted from lidar data collected in 2000, 2010-2012, parts of 2016, and 2019.

For this project, the original paper maps were again scanned at 600 dpi to create a digital image, georeferenced in NAD27, and transformed into the NAD83 coordinate system. The shoreline positions on the paper maps were compared with the shorelines that were contained in the Bureau database. In some instances, particularly along the bay shorelines, positions were revised if they did not match with the database. In other instances, older shorelines that were notated on the paper maps were not included in the digital database. They were digitized and added to the data for the park. The georeferenced 1937 and 1958 photos were also used to verify shoreline positioning. In areas where there were differences between the paper maps and the georeferenced photographs, the shoreline position from the photomosaics were digitized in ArcGIS. By using directly georeferenced imagery, errors can be eliminated that can be introduced through the transfer to paper maps, georeferencing in the older NAD27 coordinate system, and transformation to the newer NAD83 coordinate system.

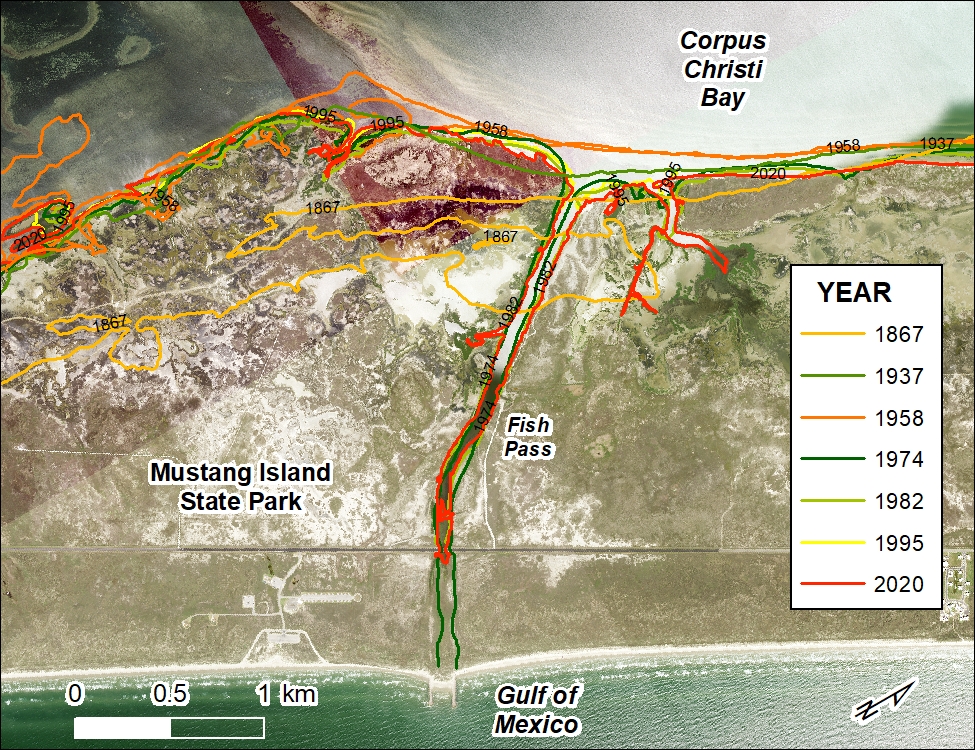

Mustang Island State Park has approximately 8.6 km (5mi) of Gulf of Mexico shoreline. These shorelines are susceptible to erosion by non-storm waves, storm surge and storm waves, and relative sea level rise. The Corpus Christi Bay shoreline in the state park is characterized by back-barrier salt marsh, wind tidal flats, and narrow bay-margin beaches. Bay-margin marshes and tidal flats have low elevation, minimal slope, and muddy sand or sandy mud substrate. These shorelines are highly susceptible to erosion by non-storm waves and to land loss by submergence related to relative sea level rise. They have a low susceptibility to erosion related to storm surge and storm waves because they are inundated before storm passage. The exception is if the shoreline is near a washover channel. Then they are highly susceptible to change due to storm surge and waves. The position of the bay shoreline has experienced significant positional change between 1867 and 2020 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Position of Corpus Christi Bay margin shorelines along a portion of the Mustang Island State Park shoreline between 1867 and 2020.

Shoreline Movement

Texas coastal shorelines include bay and Gulf of Mexico frontage along the barrier islands and mainland shores. In Mustang Island State Park, these shorelines include Gulf beaches, salt marshes, wind tidal flats, and bay beaches. Common coastal processes that include wind-driven waves, storm surge and storm waves, and relative sea-level rise contribute to the dynamic nature of these coastal boundaries, leading to shoreline retreat or advance through removal or addition of sediment, or by submergence and emergence. It is important to monitor the movement of these coastal boundaries, determine coastal land loss and gain, and characterize shoreline movement and its potential impact on the varied activities, uses, and functions of coastal land, vegetation, and habitat.

Bureau researchers conduct studies that update rates of shoreline movement; characterize shoreline types; and access shoreline vulnerability to sea-level rise, non-storm waves, and storm surge and waves. The most recent update to Gulf of Mexico shoreline movement for the entire Texas coast was completed through 2019 (Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021). The last study to look at shoreline change in Corpus Christi Bay was completed in the 1980s (Morton and Paine, 1984). For this project, long-term and short-term Gulf and bay shoreline change rates were calculated based upon the shorelines assembled for this project.

Calculating rates of shoreline movement starts with importing shorelines into an ArcGIS geodatabase, then creating a baseline to cast shore-parallel transects using the GIS-based extension software Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS v. 5.1; Himmelstoss and others, 2021). Transects were cast at 25-m intervals along Gulf of Mexico shorelines and 50-m intervals along the bay shoreline. Rates of change and associated statistics for the 1937 to 2022, 1958 to 2022, and 2000 to 2022 periods were calculated using the transect locations and the selected shorelines for the Gulf shoreline. Rates of change and associated statistics for the 1937-2020, 1958-2020, and 1982-2022 periods were calculated for the bay shorelines. The intersection of the transect lines with the latest shoreline was used to create GIS shape files containing the rates, statistics, and period of shoreline change measurements and the measurement transects bounded by the most landward and seaward historical shoreline position for each measurement site. For additional information and details regarding Texas Gulf and bay shorelines and calculating shoreline change rates, see Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021 as well as the Bureau’s Texas shoreline change website (https://www.beg.utexas.edu/research/programs/coastal/the-texas-shoreline-change-project). To learn more about shoreline change in recently studied Texas bays, see Caudle and Paine, 2024 (Galveston Bay); Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2016 (Copano, San Antonio, and Matagorda Bays); as well as the Bureau’s Texas bay shoreline change project website (https://www.beg.utexas.edu/research/programs/coastal/texas-bay-shoreline-change).

According to the most up-to-date movement calculations for the entire Texas Gulf of Mexico shoreline (from Sabine Pass at the Texas/Louisiana border to the Rio Grande at the Texas/Mexico border), the average rate over the longer-term monitoring period (1930s to 2019) is retreat at 1.27 m/yr (4.2 ft/yr), over the intermediate-term monitoring period (1950s to 2019) is retreat at 1.42 m/yr (4.7 ft/yr), and for most recent, short-term monitoring period (2000 to 2019) is retreat at 1.25 m/yr (4.1 ft/yr) (Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021). For these same time periods, Mustang Island shorelines retreated at a low net rate of 0.29 m/yr (0.7 ft/yr) between the 1930s and 2019, averaged a higher rate of retreat of 0.72 m/yr (2.4 ft/yr) between the 1950s and 2019, and a slight net advance at 0.15 m/yr (0.5 ft/yr) during the most recent monitoring period (2000 to 2019, Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021). Mustang Island was one of only two geologic features on the Texas coast that had net shoreline advance from 2000 to 2019 (Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021). Shoreline change rates along the Gulf of Mexico coast in Mustang Island State Park averages minimal retreat (moving landward) at 0.39 m/yr (1.28 ft/yr) between 1937 and 2022 (Fig. 2). Between 1956 and 2022, that rate increases to 0.84 m/yr (2.74 ft/yr) of retreat. For the most recent monitoring period, 2000 to 2022, the shoreline retreated at a much lower rate, 0.12 m/yr (0.39 ft/yr). The shoreline in the state park reported slightly higher rates of retreat than the average rates for Mustang Island over all three monitoring periods, but significantly lower rates when compared to the whole Texas coast.

Shoreline change rates for the Corpus Christi Bay coastline in Mustang Island State Park averaged low rates of retreat, 0.23 m/yr (0.74 ft/yr), for the longest-term (1937 to 2020) monitoring period (Fig. 2). The rate increased for the 1958 to 2020 monitoring period to 1.18 m/yr (3.86 ft/yr) of retreat. During the most recent monitoring period, 1982 to 2020, the net average rate of change along the back-barrier island shoreline switched to advancement at 0.28 m/yr (ft/yr). Shoreline types along Corpus Christi Bay coastline include narrow beaches or spits at 29% of sites, salt marsh at 63% of sites, and wind tidal flats at 9% of the sites in the state park. Table 1 shows the net average rate of shoreline movement along those shore types over the three monitoring periods.

Figure 2. Net rate of long-term movement for the Gulf of Mexico shoreline and the Corpus Christi Bay shoreline in Mustang Island State Park. The Gulf rates were calculated from shoreline positions from 1937 and 2022 and the bay rates were calculated from shoreline positions from 1937 and 2020.

| Bay-margin Shore Type |

1937-2020 | 1958-2020 | 1982-2020 | |||

| m/yr | ft/yr | m/yr | ft/yr | m/yr | ft/yr | |

| Beach or Spit | -0.79 | -2.58 | -1.79 | -5.87 | 0.67 | 2.20 |

| Marsh | 0.13 | 0.43 | -0.84 | -2.74 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Tidal flat | -0.94 | -3.08 | -1.59 | -5.21 | 0.90 | 2.94 |

Volumetrics

Volumes and their relationship to elevation help identify areas where sediment has accumulated, as well as areas where little sediment is stored near the shoreline. Peak elevations along the foredunes help identify areas susceptible to breaching and overwash during tropical cyclone passage. The Bureau calculated volumetrics data from the 2019 lidar data which is presented as peak elevations along the Texas Gulf shoreline and as volumes above threshold elevations ranging from 1 to 9 m (3 to 30 ft) relative to the NAVD88 elevation datum (Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021). These volumes can be cast as total volume above a threshold elevation for a given shoreline segment, or as “normalized” alongshore volumes above a threshold elevation, calculated by dividing the volume within the shoreline segment by the alongshore length of the segment. Peak elevations and normalized volume above 1 m elevation along the shoreline are presented in the state park online viewer. To view shoreline movement rates and volumetrics data for the entire Texas coast, visit the Bureau’s Texas shoreline change project interactive map (https://coastal.beg.utexas.edu/shorelinechange2019/).

Peak elevations and beach and foredune volumes generally increase southward toward the central Texas coast, where Mustang Island is located. Peak beach and foredune elevations are relatively high along nearly all of Mustang Island. Peak elevations are above 7.5 m (24.6 ft) along 50% of the Mustang Island shoreline, much higher than the whole-coast average (Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021). Within the state park, peak elevation averages 6.7 m (22 ft) with about 50% of the shoreline having peak dune crests above 7 m (23 ft).

Beach and dune system sediment volumes above 1 m (3 ft) of elevation follow a similar trend to the peak elevations: beach and foredune volumes are high along the entirety of Mustang Island. Along the Texas Gulf shoreline, the average volume of sediment above 1 m (3.3 ft) elevation per meter alongshore is about 230 m3/m (70 yd3/ft, Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021). For Mustang Island, the average volume of sediment above 1 m (3.3 ft) elevation per meter alongshore is 457 m3/m (183 yd3/ft, Paine, Caudle, and Andrews, 2021). Along the 5 miles of state park shoreline, the average volume of sediment is 466 m3/m (186 yd3/ft). All of the sites in Mustang Island State Park have sediment above the 4.5 m (14.8 ft) elevation threshold.

References

Caudle, T. L., and Paine, J. G., 2024, Historical Shoreline Movement in Galveston, Trinity, East and West Bays on the Upper Texas Gulf Coast: The University of Texas at Austin, Bureau of Economic Geology, Final Report prepared for Texas General Land Office, under contract no. 23-020-016-D610, 94 p.

Himmelstoss, E.A., Henderson, R.E., Kratzmann, M.G., and Farris, A.S., 2021, Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS) version 5.1 user guide: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2021-1091, 104 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20211091.

Morton, R. A., and Paine, J. G., 1984, Historical Shoreline Changes in Corpus Christi, Oso, and Nueces Bays, Texas Gulf Coast: The University of Texas at Austin, Bureau of Economic Geology, Geological Circular 84—6, 66 p.

Paine, J. G., Caudle, T., and Andrews J., 2016, Shoreline Movement in the Copano, San Antonio, and Matagorda Bay Systems, Central Texas Coast, 1930s to 2010s: The University of Texas at Austin, Bureau of Economic Geology, Final Report prepared for General Land Office under contract no. 13-258-000-7485, 72 p.

Paine, J. G., Caudle, T., and Andrews, J. R., 2021, Shoreline Movement and Beach and Dune Volumetrics along the Texas Gulf Coast, 1930s to 2019: The University of Texas at Austin, Bureau of Economic Geology, Final Report prepared for Texas General Land Office, under contract no. 16-302-000, 101 p.