Dinosaur Footprints

What and Why

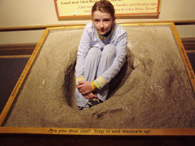

Child of WPA workers sitting in a dinosaur footprint. Photo from Paluxy river quarry by R.T. Bird from the collection of Wann Langston.

Trackway at Dinosaur Valley State Park, Blue Hole.

Bipedal three-toed track maker.

What?

They walked all over Texas...

120 to 100 million years ago, dinosaurs lived in the coastal shallows and offshore islands of Texas and left footprint evidence for geodetectives to investigate.

Why?

Trackways help us learn more about dinosaurs and to walk in their footsteps. More information about the geography and geology pertaining to this map can be found on the FAQ page.

Photos by Sue Hovorka unless otherwise noted. Click on images to view larger.

Where

Click on thumbnail for location map showing all known trackways, along with other places where you can view dinosaur tracks

Where?

Tracks are found all over the areas of the state where Lower Cretaceous rocks are exposed.

Places in Texas to see dinosaur trackways:

Dinosaur Valley State Park

This State Park, 60 miles southwest of Fort Worth on the Paluxy River, preserves one of the most famous trackways in the world. Take your wading shoes and swimsuit to walk where the dinosaurs walked. Signage, a visitor center, and dinosaur models make this a good study trip, not to mention the swimming hole, a river for fishing, and a campground.

Background information for Dinosaur Valley State Park

Making footprints

Probably an acrocanthrosaur trail which goes on uninterrupted for over 400 feet. Photo courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept.

Photo courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept.

Theropod tracks at low water. Photo by R.T. Bird from the collection of Wann Langston

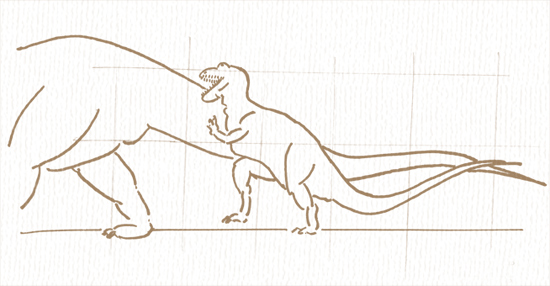

Drawing by R.T. Bird of historic Paluxy River trackway showing areas to be quarried for museums.

Dinosaur Valley State Park

The Dinosaur Valley State Park trackway is famous as a well-preserved site of very large sauropod dinosaurs. The tracks are preserved in the Lower Cretaceous Glen Rose Formation in the river bed. Rear footprints of the sauropods are as much as 3 feet in diameter and 18 inches deep. Well-preserved tracks of more commonly found three-toed dinosaurs are found here also.

Geologic history

About 120 million years ago, soft, muddy lime sediment was deposited in bays and lagoons on the west shore of a shallow sea. Groups of dinosaurs walked here across the soft mud while it was still wet. If you try walking in soft mud, you can make the mud squish out from under your feet and between your toes just like it did for the dinosaurs (see photo). Fine clayey and silt sediments washed in from land areas to the north and west and quickly buried the tracks. Beaches or lime sand bars were formed as more marine conditions slowly returned.

Lime sediments were quickly cemented to form moderately hard limestone. The fine clayey and silt sediments became weak shaly rocks. Erosion of the Paluxy River has exposed these sediments, easily stripping off the shale but leaving limestones in ledges to form the hard floor of the river (see photo).

UT's historical involvement in these tracks

R. T. Bird, fossil collector for the American Museum of Natural History in New York, visited the track site and worked with E. H. Sellards (former director of the Bureau of Economic Geology and the Texas Memorial Museum) at The University of Texas at Austin to organize collection of the tracks. In 1940, three large areas of tracks were cut loose by workers employed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which provided employment to people who needed work during the Great Depression. One set of these tracks is conserved by the Texas Memorial Museum on The University of Texas at Austin campus. Other individual tracks went to Baylor University in Waco, Texas; Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas; the American Museum of Natural History in New York; the U.S. National Museum in Washington, D.C.; and Brooklyn College, New York. R. T. Bird carefully sketched the site and labeled the limestone blocks for reassembly.

Texas Memorial Museum Trackway Exhibit

Part of the Paluxy River trackway was removed in 1940 and assembled as an exhibit on the University of Texas, Austin, campus. After you see the tracks, you can visit the museum and see fossil bones of Cretaceous animals similar to those that made the tracks. You can also see fossils of other ages.

Background information for Texas Memorial Museum trackway exhibit

WPA workers excavating Paluxy River trackway. Photo by R.T. Bird from the collection of Wann Langston.

Theropod teeth. Tyrannosaurus maxilla, Cretaceous, Brewster County, Texas. On display at the Texas Memorial Museum.

Texas Memorial Museum trackway exhibit

During the Great Depression, WPA workers removed two chunks of the Paluxy River trackway and moved it to two museums, one of which was the then-brand-new Texas Memorial Museum. The tracks are housed in their own building on the north side of the main museum building, where they can be viewed through a glass window.

Deep holes were made by the front feet of a sauropod, which were smaller than its very large rear feet. After the sauropod passed by, a somewhat smaller dinosaur came along, walking on its hind feet, which had three toes with sharp claws. This was most likely a theropod dinosaur. See teeth of a theropod inside the museum (see photo)

The Texas Memorial Museum has plans to move the tracks to a more prominent viewing area, where they can be better protected from the moisture that might cause degradation.

Heritage Museum of the Texas Hill Country

This small museum has several sets of tracks on the grounds, as well as other local nature and history information.

Background information for Heritage Museum of the Texas Hill Country

Heritage Museum of the Texas Hill Country

The trackways at this site were exposed in the early 1980's, during road construction and clearing of a level area. These tracks in the Lower Cretaceous Glen Rose limestone were made by a bipedal, three-toed dinosaur, which have been identified as most likely belonging to a therapsid, or possibly an ornithopod.

A layer of mudstone overlies the trackway (see photo).

The property has passed through the hands of several owners, and the tracks have been degraded somewhat by weathering and attempts to preserve them, but they are nevertheless interesting to see. The small museum is also a resource for other local nature and history information.

Plans are under way to excavate the hillside where the tracks disappear. Keep an eye on this site, and you could be one of the first humans to see a track that has been buried for 100 million years.

Hartman Prehistoric Garden at Zilker Park

Tracks found here in 1992 were too fragile to be preserved after they were exposed. While you are looking at the replica tracks there, visit the beautiful garden to see plants that are descendants of plants that lived at the time of the dinosaurs.

Background information on Hartman Prehistoric Garden

Ornithomorphid dinosaur sculpture by John Maisano, Hartman Prehistoric Gardens, Austin Texas. Compare this track maker with the modern bipedal track maker here.

Horse tails (Equisetopsida). This still-common plant has a lineage of even greater antiquity than that of the dinosaurs!

The magnolia is a flowering plant that was newly evolved during the time of the dinosaurs. The one in the photo is called a banana magnolia for the fragrance of its flowers during the spring.

The saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), a plant of today that dates back to the Cretaceous, is displayed at the Hartman Prehistoric Garden.

Hartman Prehistoric Garden

In 1992, volunteers at Zilker Botanical Garden in south Austin were tidying the quarry that had been historically used to supply flagstone for walkways and buildings in the garden, when they uncovered tracks of some three-toed dinosaurs. Rains had washed away the soil and thin-bedded, clayey limestone, thus exposing about 100 tracks made by probably six bipedal, three-toed dinosaurs. These tracks are unusual because they occur in limestones mapped as the Lower Cretaceous Edwards Formation, which is slightly younger than the Glen Rose Formation.

Because the tracks started degrading during exposure, the Austin Area Garden Council decided to cover them and plant a garden that would help visitors imagine what it would have been like to walk through a Cretaceous forest with the dinosaurs. The nearest living relatives of the plants that dominated the Cretaceous landscape were planted, which include relatives of very old species, such as magnolias, cycads, ferns, and primitive grasses, as well as pines, junipers, and yews.

One possible track maker is the theropod Ornithomimus, a life-size sculpture of which lurks amid the cycads. What other treasures can you find in the garden? Go to the Activities page to find a Treasure Hunt of the Hartman Prehistoric Garden.

Places in Texas to see fossilized bones of dinosaurs:

Model of vertebrate exhibits on the lower floor of the Texas Memorial Museum.

Track cast at the Witte Museum in San Antonio.

Perot Museum of Nature and Science has one the state's best displays of fossilized bones of dinosaurs and other animals that roamed across Texas during the Cretaceous. Acrocanthosaurus, Tenontosaurus , and an as-yet-unnamed, plant-eating ornithischian made three-toed tracks. Alamosaurus, a sauropod, would have made larger, rounded prints. Several samples of tracks are found within this exhibit.

Fort Worth Museum of Science has a new exhibit, with which visitors can interact by working as scientists, including newly identified skeletons thought to be track makers.

Houston Museum of Natural Science has a large exhibit of 450 specimens and replicas. Most of these skeletal fossils are from other parts of the world. Be prepared to find and enjoy the “Chromosaurs” on the museum grounds.

Museum of Texas Tech University exhibits specimens from every period of the Mesozoic Era. Featured are fossils from the Museum's special area of research, the Triassic of West Texas, Lubbock, Texas.

Texas Memorial Museum has recently updated its exhibit featuring Texas fossils grouped by geologic age, including track makers, fossil plants, and other associated animals.

The Witte Museum, San Antonio, has a few casts of tracks that you can try out, too.

FAQ

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. What kind of dinosaurs made tracks?

A. Nobody knows exactly what species made the tracks, but vertebrate paleontologists can make a good guess.

The match between fossil track and fossil skeleton is rarely 100%. Vertebrate paleontologists respect this uncertainty by classifying tracks as ichnotaxa–Grallator , for example (for three-toed, bipedal tracks), or Brontopodus (large quadrupedal tracks). The scientists then speculate about exactly which fossil skeletal remains might be from which animals making the tracks. Then, using skeletal fossils to go by, they consider what animals are known to have been alive at the time the tracks were made and in the same general area as the trackway. Sometimes the best match is to a large group of dinosaurs. Remember that skeletal remains and trackways are incomplete records of the past because preservation requires a lucky coincidence of events. Many species most likely lived and became extinct without a trace.

Also, most skeletal remains are incomplete; small foot bones may not have been preserved with the rest of the skeleton. But if a match can be proposed, it provides additional information about how to better understand the skeleton—how the animal moved, whether it stood upright, and what the long-gone skin and muscles of its feet looked like. Matching tracks to fossilized skeletons has let vertebrate paleontologist better reconstruct dinosaur skeletons in museums and better draw the animals in their habitat.

Two main types of track makers were common in the Cretaceous of Texas-animals that walked on four feet (quadrupedal) and those that walked on their two hind feet (bipedal).

Bipedal tracks in the Cretaceous rocks of Texas probably were made by several groups of dinosaurs, including theropods and ornithopods. These dinosaurs, like birds of today, walked on their toes, leaving three-toed prints. Comparing the teeth of these dinosaurs with animals living today reveals that the dinosaurs were probably carnivorous. Vertebrate paleontologists have proposed that the Glen Rose theropod track maker that had sharp toenails could have been Acrocanthosaurus. Other possible track makers are shown at the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History. Blunter three-toed tracks could have been made by the ornithopod from a group known as Iguanodons. Smaller three-toed tracks might have been made by young members of these species or by any one of a number of smaller bipedal dinosaurs.

Quadrupedal tracks are interpreted as the tracks of sauropods—large, long-necked dinosaurs. Dinosaur researchers propose likely makers of the tracks at Dinosaur Valley State Park are Pleurocoelus or Sauroposeidon. The skeleton of a proposed sauropod track maker is on exhibit at the Fort Worth Museum of Science and Technology. Large (3-foot-wide) depressions were made by hind feet. Prints of front feet are somewhat U shaped, but they have sometimes been damaged or eliminated by the hind footprints coming after and obliterating them. The animals' peglike teeth suggest that they browsed on shrubs and other vegetation.

Q. How much did dinosaurs weigh?

A. Comparing the size of the footprint and length of the animal's stride with those of modern animals having similar locomotion helps scientists estimate the size of the track-making animal.

The largest sauropod track makers had hind footprints about 3 feet across and 18 inches deep and strides of as much as 10 feet. These giants weighed 30 tons and may have been more than 40 feet long. The three-toed track-making animals were smaller, making tracks 20 inches across and 5 inches deep. Their weight is estimated to be as much as 2 to 3 tons and their length as much as 25 feet. However, the stride in these trackways is as much as 9 feet, nearly as long as that of the sauropods, showing that the bipedal dinosaurs had a more efficient gait and they may have been capable of greater speed! You can estimate how fast a dinosaur moved from its foot size and stride length. See instructions here (PDF).

Q. What do scientists learn from trackways?

A. Tracks provide direct information about how animals behaved that is difficult to get from fossil skeletons.

Trackways have helped researchers understand that both plant-eating and meat-eating dinosaurs carried their large, long tails in the air. Some early paleontologists thought that these massive tails must have dragged behind the animal. However, track studies show that tails rarely made drag marks behind the animal, although marks interpreted to be prints of a slashing tail have been found and interpreted as an indication that the animals may have used their massive tails defensively.

Trackways have helped researchers confirm that although they were very large compared with most animals today, dinosaurs were strong enough to walk on land. Some earlier workers thought that such large animals would not have been able to move on land, and they would therefore have lived mostly in water.

Trackways have helped researchers show that dinosaurs stood upright like elephants of today. Some early reconstructions showed dinosaurs having a squat stance, with their legs to the sides and bellies nearly dragging the ground, like crocodiles'. However, width of trackways shows that dinosaurs' legs were underneath their bodies.

Trackways have helped researchers suggest that carnivorous dinosaurs could move rapidly, with 9-foot strides.

Trackways have helped researchers show the arrangement of skin, muscle, and other soft tissue on their feet and hip height of the animal.

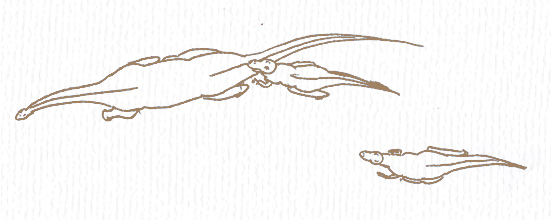

Display at the DVSP visitor center shows how vertebrate paleontologists match casts of skeletal bones to casts of tracks—Bipedal three-toed track maker.

Shows how the World's Fair artists reconstructed the theropod foot.

Shows how the World's Fair artists reconstructed the sauropod foot.

Sauropod

Q. What kept dinosaurs from walking all over the state?

A. You may have noticed that the tracks are mostly in one part of Texas, stretching from Pecos County through San Antonio, north to Dallas and into Arkansas. Why are tracks not found in Houston, Midland, and Lubbock?

One reason is that this belt of rock is an outcrop of rocks of Lower Cretaceous age, which was deposited during the Mesozoic, the "age of dinosaurs." The rocks of the Llano region and parts of west Texas are too old-dinosaurs (in fact most land-dwelling species) had not yet evolved when these rocks were deposited. The rocks of the top of the High Plains and across the Gulf of Mexico coastal plain are too young, deposited after dinosaurs were extinct.

West of the area where tracks are found, Lower Cretaceous rocks have been eroded. East of the area, Lower Cretaceous rocks have been buried. So although dinosaurs most likely walked all over Texas, the only place that we can see evidence is in the middle of the state.

Habitat during the Early Cretaceous was suitable for dinosaurs. During the Early Cretaceous, Texas was on the coast of a shallow ocean at 25° north latitude (a little further south than Texas is now). Dinosaurs left their tracks on muddy flats and in shallow water on an extensive plain. Preserved coaly layers record vegetation that grew in swamps along this coast. Younger Middle and Upper Cretaceous rocks were deposited mostly in marine environments, so the fossils they contain are of marine reptiles—the Onion Creek mosasaur, for example.

Farlow, J. O., 1993, The dinosaurs of Dinosaur Valley State Park, Somervell County, Texas: Austin, Texas, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, unpaginated.

Activities

Activities: studying animal behavior from trackways

Photograph of cleaned section of sauropod tracks, Davenport Ranch in Medina County.

Making your own tracks: a do-it-yourself experiment. [PDF]

Digging up Dinosaurs [Information on museums PDF]

A number of museums have dinosaur digs, where students can excavate fossil replicas from sand, including

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt

Find these things in the garden, then click on the numbers below the map to find out what the clue tells you about dinosaurs. To download a printer-friendly PDF of this activity to take with you to Hartman Garden, click here.

1

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #1

Glassy volcanic rock shot through with white calcite veins and xenoliths (foreign rocks) of olivine. This large black rock represents the Cretaceous volcanoes that were active at the time of the dinosaurs.

2

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #2

Sand-size grains of broken shells were deposited as lime sand on a Cretaceous offshore bar. A chemical reaction occurred sometime not long after deposition cemented it into the hard limestone.

3

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #3

This microcave has a pale orange filling and mini-stalactites and stalagmites. The calcite below it, probably also a cave fill, has beautiful white calcite crystals. The limestone was deposited during the Cretaceous, at the time of the dinosaurs, but the caves formed much later.

4

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #4

Water has dissolved a crack through the Edwards limestone. Sit here and think about how fast it dissolves. The caves are much younger than the dinosaur footprints that are in the rock. Imagine how long ago dinosaurs were walking around!

5

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #5

The Prince Sago, a large tree fern, was an important part of the Mesozoic landscape. This one was imported from Taiwan . Do you think dinosaurs could have eaten them?

6

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #6

Fossilized wood (also called petrified wood ) is ancient wood that has been replaced by minerals, mostly fine-grained quartz. Plant fossils like these help us reconstruct the ecosystems of dinosaurs.

7

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #7

The magnolia is a flowering plant that was newly evolved at the time of the dinosaurs. This one is called a banana magnolia because of the fragrance of its flowers in spring.

8

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #8

Insects were an important part of the Mesozoic landscape; they predate the prehistoric garden.

9

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #9

Limestone is a rock created mostly by living things. These high-spired snails (gastropods) grazed on algae and are common near trackways.

10

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #10

Trackways of a three-toed dinosaur are copies made in slightly harder limestone than the originals. If you look closely you can see the saw and chisel marks, which tell you that they are copies. How many can you find in the garden?

11

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #11

Chert nodule in limestone. This hard rock, also called flint, is formed of microcrystalline rock that was used by Native Americans to make arrowheads.

12

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #12

This force of nature is important in exposing trackways at the surface and adds to any garden.

13

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #13

Horsetails are ancient plants that evolved even before the dinosaurs, during the Carboniferous Period.

14

Hartman Garden Geo Treasure Hunt #14

Replica of a fossil turtle shell found during the excavation of dinosaur tracks. The turtle was part of the dinosaur ecosystem. The display at the Texas Memorial Museum shows how fossil fragments of a turtle were reconstructed.

Rock and Soil Facts

Rock Sediments and Soil Facts

Limestone and mudstone. One key to good exposure of trackways is layers of soft mudstone on top of relatively hard limestone.

Photo courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept.

Rocks that contain tracks

Most Texas dinosaur tracks are in limestone that formed in shallow water at the edges of an ocean. Limestone is a type of rock created mostly by living things, such as calcareous algae, corals, oysters, and clams. Shells and hard limey stems and fronds were broken into sand-sized grains and even mud-sized particles. The sediment was deposited in the dry or shallow-water coastal environments where dinosaurs roamed. Storms would blow in and deposit new layers of sediment on top of the dinosaurs' footprints, burying the prints and preserving them.

Erosion and deposition of gravel, sand, silt, and clay

Dinosaur tracks are covered and uncovered by erosion and deposition of gravel, sand, silt, and clay. Fossil hunters love rivers because they cut down through rock layers and expose rock surfaces that have been buried for millions of years-although once they have exposed the fossils, rivers will continue to erode, destroying what they have exposed, eventually revealing the layer beneath.

The gravel, sand, silt, or clay that is deposited by rivers is called alluvium. Alluvium is classified first by grain size and second by what the grains are made of. Gravels have the largest grain size and in Texas are most commonly made of quartz, chert, and limestone pebbles. Sand and silt are composed mostly of quartz, and clay is composed mostly of clay minerals.

Geodetective

Geodetective

Drawing by R.T. Bird of historic Paluxy River trackway showing areas to be quarried for museums.

Photo by R.T. Bird of the same area seen in the drawing above.

Trackway from the Dinosaur Valley site which is now preserved at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Photo by R.T. Bird.

What is a geodetective?

You probably learned in school that scientists follow the scientific method: (1) start with a hypothesis and an experimental method, (2) do the experiment, (3) make measurements and observations, and (4) draw conclusions to prove or disprove the hypothesis. Many geologists don't work this way. They first observe results of a series of events that happened in the past. The results are clues that then help them figure out what happened. In some ways geologists are like detectives, looking for clues left at the "scene" of an ancient event.

What are the clues from these tracks?

Look at the photograph and drawing on the right. The original researcher working at the Dinosaur Valley site on the Paluxy River selected this slab of rock to break loose and preserve in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and in the Texas Memorial Museum in Austin, because he saw a "crime" preserved in the rock. Can you figure out what happened here?

Tips:

- How many types of animals made tracks here?

- In what order were the tracks made?

- Looking at the picture, make a drawing of each animal as it walked through the mud.

- Can you and a few friends reenact what happened?

- What can you guess about the relationship among the animals?

- What things can you tell for sure?

- What things are guesses?

One answer:

When R.T. Bird drew sketches of the trackways, this is what he thought about. Is this the way it really happened?

When R.T. Bird drew sketches of the trackways this is what he thought about:

1. "A wounded or age-feebled sauropod trailing [the] rest of [the] escaping 'herd' is singled out for attack by two carnosaurs, one of which seizes the monster by tail near [the] body and attempts restraining action."

2. The resisting sauropod is …"pulled slightly off course to the left as second carnosaur (tracks under spoil bank) circles, intending a throat hold."

3. The first carnosaur keeps his grip on the sauropod while the second carnosaur fails to reach the victim's neck.

4. "…after a few steps the sauropod pulls free." The carnosaur …" receives [a] slashing blow from sauropod's tail just before both trackways disappear."

Lesson Plans

Photo by R.T. Bird from the collection of Wann Langston.

Photo courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept.

Photo courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept.

Lesson Plans

Click the buttons below to download lesson plans in PDF format.

Resources

Websites with pictures and information about dinosaurs and dinosaur trackways

- Enchanted Learning.com

- Texas Parks and Wildlife Kids' Page

- Ocean Dallas: National Earth Science Teachers Association Field Trip Guide (PDF, 2005)

- Virtual Geology Field Guides to the USA

- An Overview of Dinosaur Tracking

- Perot Museum of Nature and Science

- Fort Worth Museum of Science

- Shuler Museum of Paleontology at SMU

- Texas Memorial Museum

- Museum of Texas Tech University

Books

- Farlow, J. O., 1993, The dinosaurs of Dinosaur Valley State Park, Somervell County, Texas: Austin, Texas, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, unpaginated.

- Finsley, C. E., 1999, Discover Texas dinosaurs: Houston, Texas, Gulf Publishing Company, 150 p.

- Jacobs, Louis, 1995, Lone star dinosaurs: College Station, Texas, Texas A&M University, 160 p.

- Zappler, George, 2001 (revised), Learn about... Texas dinosaurs: Texas Parks and Wildlife Press,

48 p.