Introduction to Carbonate Environments, Facies, and Facies Tracts

Robert G. Loucks, Charles Kerans, and Xavier Janson

Bureau of Economic Geology

| Design Objectives |

| Credits |

| Back |

| Top |

| Exit |

|

|

|

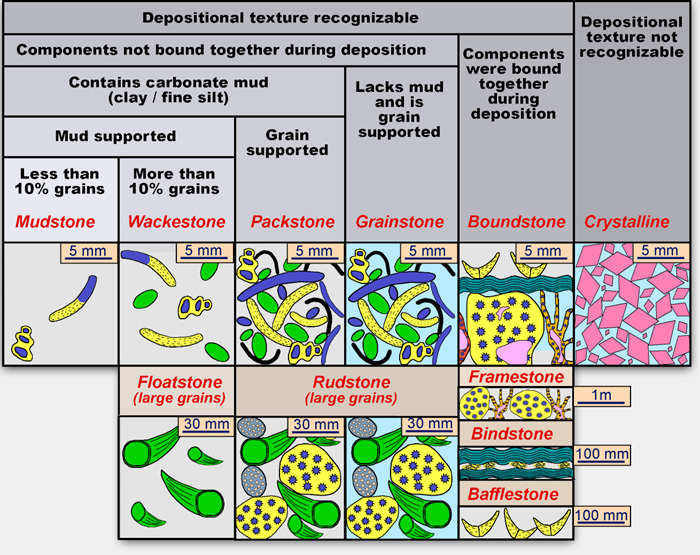

| DUNHAM’S CARBONATE ROCK TEXTURE CLASSIFICATION Dunham (1962) produced a classification of carbonate rocks that is based on depositional texture. He noted that there are several textural features that are especially useful in classifying carbonate rocks:

|

|

|

|

TEXTURE TYPES Click on terms in blue below to see captioned photo examples. Mudstone: Muddy carbonate rock containing less than 10 percent grains (Dunham, 1962). Generally indicates calm water and apparent inhibition of grain-producing organisms (low-energy depositional setting). Wackestone: Mud-supported carbonate rock containing more than 10 percent grains (Dunham, 1962). Generally indicates calm water and restriction of grain-producing organisms (low-energy depositional setting). In cases where grains are exceptionally large, Embry and Klovan (1971) designated these carbonates “floatstones.” Packstone: Grain-supported muddy carbonate rock (Dunham, 1962). Lucia (1999) divided packstones into mud-dominated (pore spaces totally filled with mud) and grain-dominated (some intergrain pore space is free of mud) packstones. This division is important in understanding reservoir quality because mud plugs interparticle pore spaces. Packstones indicate a range of depositional properties. Mud suggests lower-energy processes, whereas the abundance of grains suggests higher-energy processes. Dunham (1962) provided several scenarios for the origin of packstones: (1) they may be a product of compacted wackestones, (2) they may result from early or late mud infiltration of previously deposited mud-free sediments, (3) they may result from the prolific production of grains in calm water, or (4) they may record the mixing by burrowers of different layers of sediment. In cases where the grains are exceptionally large, Embry and Klovan (1971) designated these carbonates “rudstones.” Grainstone: Mud-free carbonate rocks, which are grain supported (Dunham, 1962). They generally are deposited in moderate- to high-energy environments, but their hydraulic significance can vary. Dunham (1962) provided several suggestions for their origin: (1) they may be produced in high-energy, grain-productive environments where mud cannot accumulate, (2) they may be deposited by currents that drop out the grains and bypass mud to another area, or (3) they may be a product of winnowing of previously deposited muddy sediments. In cases where the grains are exceptionally large, Embry and Klovan (1971) designated these carbonates “rudstones.” Boundstone: Carbonate rocks showing signs of being bound during deposition (Dunham, 1962). Embry and Klovan (1972) further expanded the boundstone classification on the basis of the fabric of the boundstone. They have three subdivisions:

Boundstones generally are deposited in higher energy environments, where currents can provide nutrients to the organisms that form the boundstone, as well as carry away waste products. Crystalline carbonates: Carbonate rocks that lack enough evidence of depositional texture to be classified. Extensive dolomitization commonly obliterates the original depositional texture.

|

| |